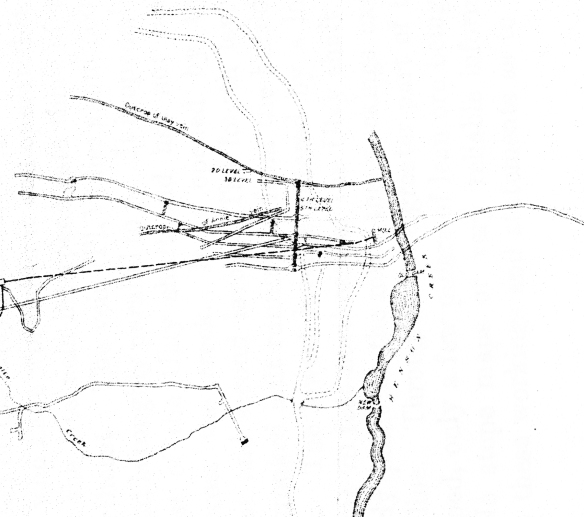

After looking, measuring, drawing, looking again, drawing again, and thinking about palindromes…. I have a drawn up a survey plan that (whilst not accurate enough to build or order materials from) is sufficiently representative of the Ute Ulay site to allow for a masterplan.

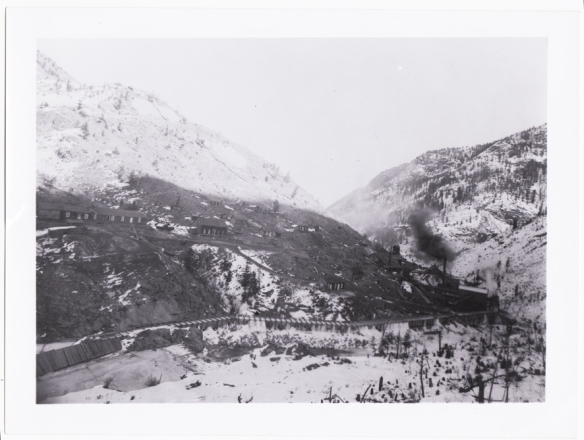

Surveys are very important documents, they often document a site immediately before change occurs. The previous landscape quickly passes into history and the survey becomes an historical document, describing the physical site at a particular point in time. They are also the starting point for landscape architectural design.

Surveying is a complex skill, which makes use of some very nifty technology. I am neither a trained surveyor, nor do I have any nifty technology (unless you count computer drawing software). My process is low tech and as accurate as my eyes and brain will allow.

In case you want to try this yourself, the process went something like this:

1. Take satellite images, USGS plans, any other plans you can lay your hands on and combine them in AutoCAD to scale.

2. Try to use on-site observations to re-draw contour lines.

3. Realise that 2. is not going to work because it is extremely difficult to determine contours by eye.

4. Draw sections to scale in AutoCAD.

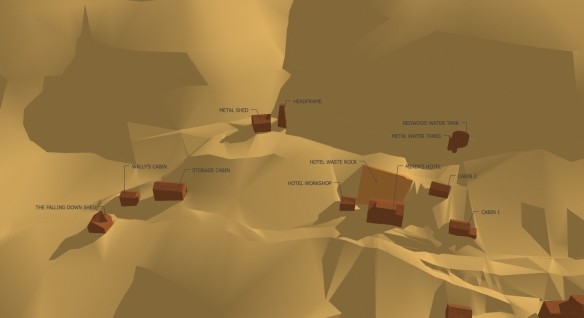

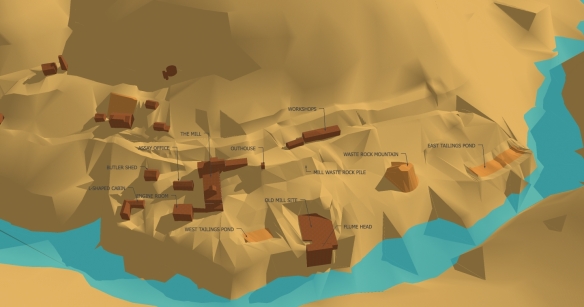

5. Take printouts of sections to the mine site and re-draw them by eye.

6. Insert 2 dimensional sections (to scale) into Google SketchUp, above the contours you already have.

7. Extrude contours up to their correct height, and alter them according to revised sections.

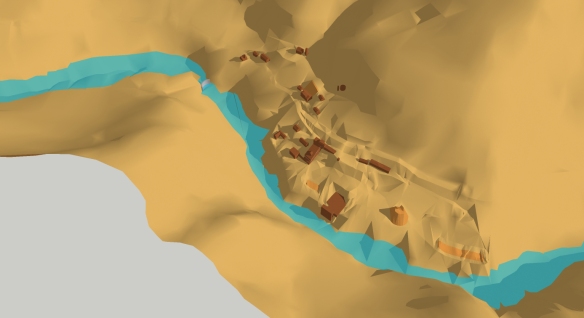

8. Create 3 dimensional model of the Ute Ulay site in Google SketchUp, and position buildings and other features onto it.

9. Slice through 3 dimensional model at 1 metre intervals (I’m definitely metric), and project slices back onto a plan.

10. Re-draw plan according to new contours in AutoCAD.